Our latest news and analysis.

How To Set The Size Of A Capital Raising.

A key question any company contemplating a capital raising needs to answer is just how much capital it should raise. In our experience, a company founder seeking advice on this topic will receive one of at least two cliched responses.

The first recommendation is to simply raise as much capital as possible. There are certainly advantages to this approach. The more capital a company raises, the more it can plough into product and business development. It can also help delay the need to raise subsequent rounds.

Raising large amounts of capital is exciting and there is undoubtedly both an ego and a PR boost for a company that pulls off a large raise. We all regularly see the headlines shouting about company X, Y or Z having just closed a multi-million-dollar round.

However, there is another school of thought that recommends raising the absolute minimum amount of capital. The thinking is that doing so reduces the level of founder dilution and also preserves their level of control over the day-to-day operations of the business.

Both perspectives have a degree of merit. However, they are also both ultimately too shallow to help founders make any concrete decisions about calibrating a capital raising.

Towards a rational framework for a capital raising

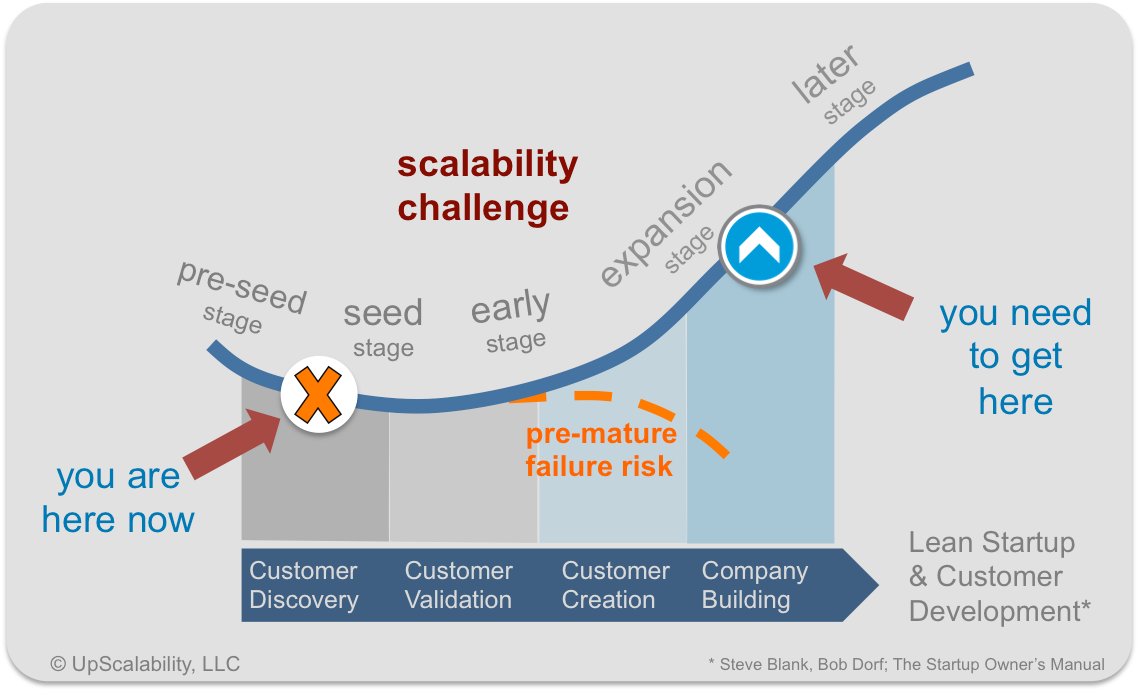

In our view, the first step to determining how much capital a business should raise is to recognise that every successful company goes through similar stages of development on the road to becoming a mature business. These stages are captured in the diagram below:

The goal of every business is to continue moving along this continuum because doing so increases the company’s value by validating its forecasts and reducing the perceived levels of risk attaching to the business.

So, the first step for any company considering a capital raising is to determine where it currently sits on this continuum because this then determines what its next immediate strategic objective or milestone should be.

For a company that has just landed on an idea, for example, the next significant step along the continuum would be to build its minimum viable product (MVP). For a company that has developed its MVP, the next step would be to try and win early customers and so on.

Having worked out what the next strategic milestone for the company is, the business then needs to scope out the operational plans needed to achieve that milestone and in turn what financial resources it will need to implement those plans.

The gap between these resource requirements and the company’s existing cash balance (and any forecast cash inflows from operations) represents how much capital the company will need to raise. If this gap cannot be met by existing sources of capital (shareholder loans, debt facilities etc.), the company will need to tap new investors.

This is the critical step in calibrating a capital raising – being able to accurately judge how much capital is needed to reach the next milestone. It’s where access to quality data and real-world experience are critical.

There is no point raising $500,000 to push into a new market when doing so will require ten-times that amount. That’s how businesses run out of cash before they achieve their desired milestones and end up seriously shaking – sometimes even catastrophically shaking – investor confidence.

As an entrepreneur, it is good to be bullish about your prospects and forecasts. Everyone likes to see ‘hockey stick’ growth. However, in calibrating a capital raising, it’s more important to be realistic in your expectations because the alternative often leads to running out of cash.

A hypothetical capital raising example

Let’s see how this all works in practice by looking at a hypothetical company – Fictitious Pty Ltd.

Fictitious is a software-as-a-service company that currently has $50,000 of cash that was originally contributed by the company’s founders. The company has a product in market and is now immediately focused on achieving its next milestone – growing its paying customer base.

To do so, Fictitious has developed a comprehensive marketing plan that will cost $50,000 over two years for both search engine and content marketing activities.

The business’ headcount will also increase from its current three full-time staff through to 12 employees that will include sales & marketing and customer success staff. To be conservative, sales are forecast to only commence by month seven of the marketing plan.

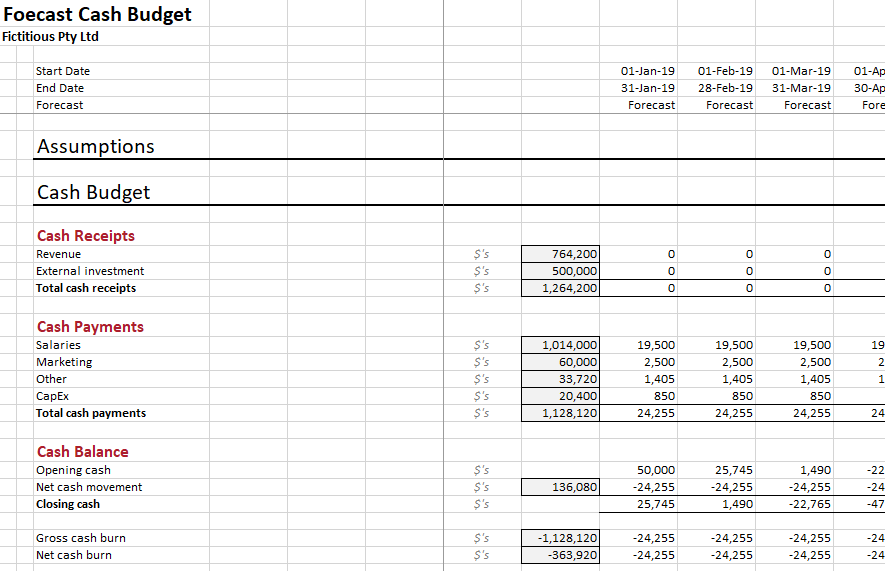

To help Fictitious decide on how much capital it might need to raise, we have built a simple financial model for the company. For a detailed article on how to build a best-practice financial model for a start-up, click here.

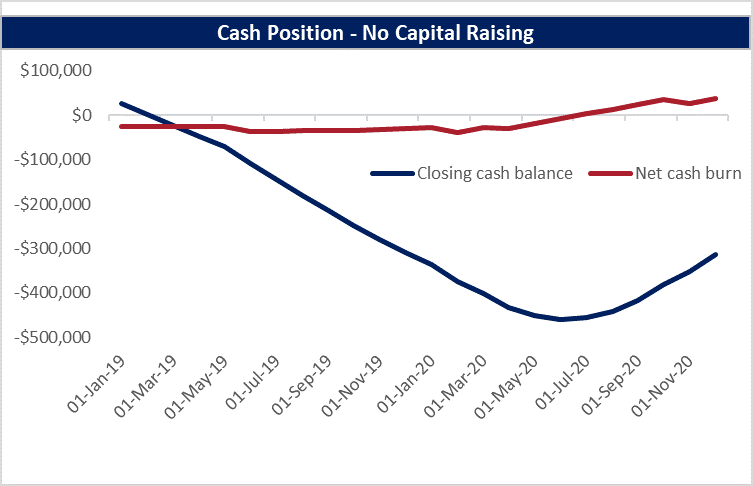

Based on its expanded marketing activities and new staff hires, the company will exhaust its existing cash reserves by the second month of the forecast period and will continue to burn cash (ie. record negative operating cash flows) for at least 18 months as shown below.

Clearly, this is not a sustainable scenario. Companies cannot run negative cash balances (assuming no overdraft is available). That’s called insolvency. So, Fictitious needs to raise external capital. The question is how much.

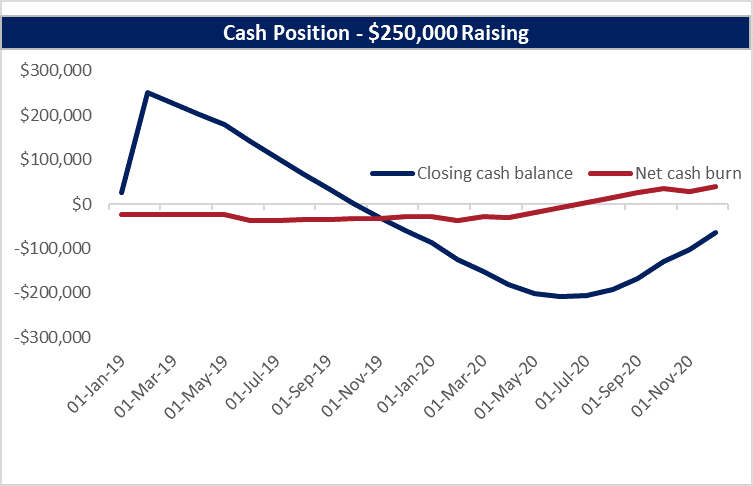

Let’s look at two scenarios – the company raising $250,000 and raising $1,000,000.

What we can see here is that raising $250,000 keeps the business’ cash balance positive for longer. However, by month 11 the company is insolvent again. Theoretically, the company could raise $250,000 now and raise more later. However, that seems to be a rather cumbersome approach.

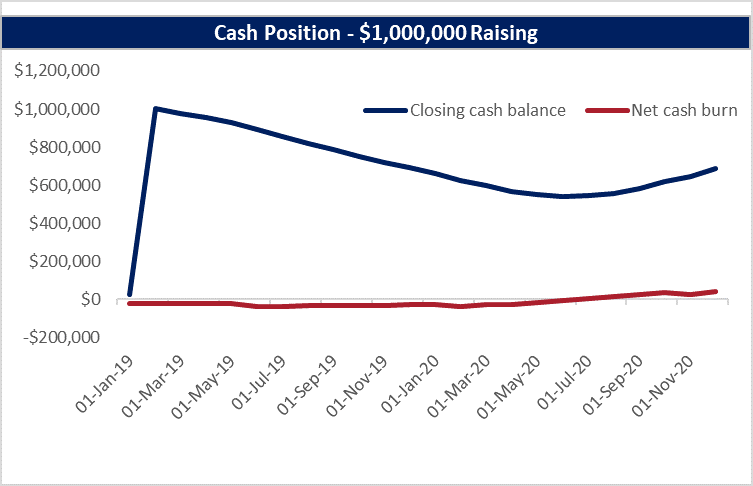

Alternatively, Fictitious could look to raise $1,000,000 as shown above. This would certainly keep the company solvent. However, the company does not seem to need that much capital. Indeed, if it raised $1,000,000, it’s cash balance would never drop below $500,000.

Assuming the company could successfully raise that amount of money, it is arguable that the level of resulting dilution would be excessive.

Some may argue that the company is better off raising the $1,000,000 and pushing aggressively for a higher pre-money valuation. That approach may have some merit. However, if the company fails to perform and needs to subsequently raise more money, the founders will be risking harsh future dilution.

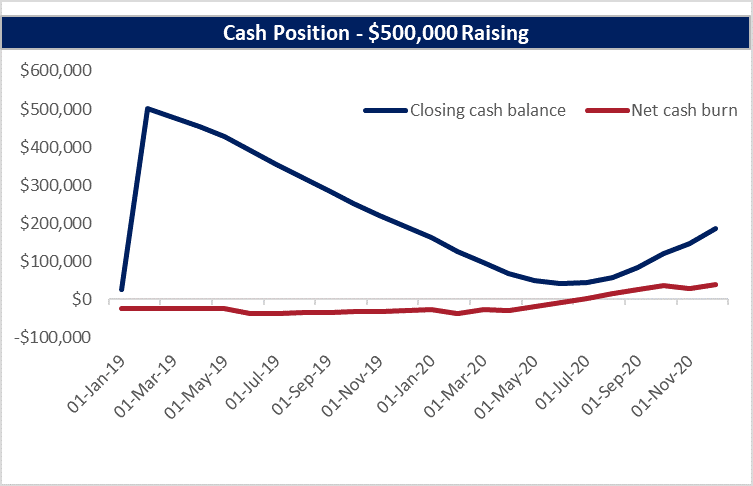

Continuing with the analysis, perhaps a capital raising of $500,000 as shown below will keep the company’s cash balance positive whilst reducing the level of dilution for the founders.

One important consideration for Fictitious is that if it raises $500,000, it’s minimum resulting cash balance will be circa $40,000 around July 2020. The company will need to decide whether that is enough of a buffer or whether a wider buffer would be more prudent.

At this point, it is also often worthwhile to run different scenarios to see how different assumptions will play out.

The lessons for capital raising

The above analysis is obviously extremely simplified. Real-world cases are far more complex with a range of factors that need to be considered, including the critical consideration of what the private capital markets will accept.

Nevertheless, the underlying logic remains sound – even when the size of the raising is many times larger than the numbers used in this post.

In considering the size of a capital raising, a company must first decide on the milestone it wants to achieve and then determine what it need to do to get there and what that will cost. The company then needs to analyse how those plans will impact its cash position going forward.

If you want to discuss how CFSG can assist you to plan for and execute a capital raising for your company, we invite you to contact us.