Our latest news and analysis.

Private Equity – What PE Funds Look For In An Acquisition

An owner considering the sale of their business typically has two broad categories of potential acquirer: strategic purchasers and private equity firms (“PE”).

To maximise competitive tension and to achieve the highest possible sale price, it is typically advisable to reach out to both strategic purchasers and private equity as part of any sound business sale process.

While business owners tend to be familiar with the idea of strategic purchasers and can often readily list a handful of potential industry players that could be acquirers of their business, they are generally far less familiar with PE and the types of businesses that they look to acquire.

What Is Private Equity?

PE are professional money managers that raise large pools of funds from private investors that are typically high net worth individuals, family offices and sizeable financial institutions such as superannuation funds and sovereign wealth funds. They then use that capital to invest in or acquire businesses with the view to ultimately exiting for large profits.

According to the Australian Private Equity & Venture Capital Association (AVCAL), PE raised $3.35b in 2017 and completed 156 separate transactions, deploying a total of $3.8b. The total amount of un-deployed capital available to PE at the end of 2017 was estimated to be $7.7b.

The ‘promise’ of PE to their investors is that the strategies and methodologies they employ have the potential to generate returns that are higher than can typically be achieved by investing in the stock market – even after allowing for the added risk of the investments being illiquid and often relatively highly leveraged.

As an example, giant US PE KKR claims gross returns of 25.6% since the firm’s inception, which is more than double the return of the S&P 500 over the same time period.

In return for managing these investors’ capital, PE managers (often referred to as general partners) charge their investors (commonly referred to as limited partners) ongoing management fees plus a success fee on the eventual profits of successfully exited investments.

It is important to recognise that while private equity tends to be longer-term investors (say, three-to-seven-year holding periods), their mandate requires them to deploy their capital and exit their investments within pre-set time limits (often 10 years from start to finish). Therefore, PE are aggressive in their pursuit of deals and every PE transaction entered into is done with a clear view to an exit.

Another important consideration for PE is maintaining a firm’s track record of success. A poor performance on an investment, let alone an entire fund, can be reputationally very damaging. As a result, PE transactions are characterised by detailed screening and significant due diligence.

Types of Private Equity Funds

There are different types of funds within the PE universe with each pursuing different types of opportunities and styles of transactions.

Venture capital firms, technically a subset of private equity, tend to make relatively small, minority stake investments in companies that are judged to have high-growth potential such as technology and life science businesses. Despite being a growing sector locally, these firms are not immediately relevant to this discussion.

Private equity, by contrast, tends to invest in more established businesses where existing owners need external capital and expertise to realise the company’s full potential (expansion stage investors) or where there is the opportunity to build value by buying out existing owners.

In expansion capital scenarios, PE may either look to take a controlling interest in the firm (i.e. >50% stake) or proceed as a significant minority investor depending on the investment mandate and the preferences of the specific PE. Either way, PE will be an active investor that will take a keen interest in the business’ growth and development.

In terms of buy-outs, depending on the appetite of the firm concerned, PE may consider acquiring both private and publicly-listed companies and either back existing management (management buy-out or MBO) or bring in an entirely new management team to run the business (management buy-in or MBI).

Whether the existing management team is retained or a new team is brought on board, the PE will look to incentivise management with a nominal equity participation. This is commonly referred to as having ‘skin in the game.’

Buy-outs also tend to be characterised by significant amounts of debt.

There are other types of funds beyond those that provide expansion capital and complete buy-out transactions. One example is funds that specialise in investing in distressed companies with the view to turning around their fortunes.

In addition to their underlying investment strategy, another way of differentiating between different funds is size – both in terms of the total amounts of capital that they have under management as well as the size of the individual investments that they make.

There are what are commonly referred to as the global mega funds that originated in the US (KKR, TPG, Carlyle etc.) but in more recent times they themselves have seen competitors emerge in Europe and Asia. These mega funds have tens of billions of dollars under management or more and seek to complete deals that enable them to deploy proportionately relevant amounts of capital. Most of these funds are active in Australia.

In addition to global funds, there are several large, local funds (PEP, Archer, CHAMP etc.) that look to invest in companies that have enterprise values from circa $100m through to about $1.0b depending on the fund.

There are also numerous funds that specifically target the so-called mid-market (Crescent, Quadrant, Advent etc.). There is inevitably a degree of cross-over between the larger funds and the self-declared mid-market funds and, indeed, often several funds will all look at and consider the same deal.

The Types of Companies Private Equity Looks For

Different opportunities appeal to different types of private equity firms. As mentioned, some will only seek larger opportunities where they can write larger-sized equity cheques whereas others will only be more constrained in terms of potential deal size.

Some PE firms tend to focus on select industry sectors such as healthcare, education, retail and so on while others are attracted to certain types of opportunities such as expansion capital, succession planning, industry roll-ups, turnarounds, leveraged buy-outs among others.

While different opportunities appeal to different PE firms, all PE opportunities tend to share several broad risk and return characteristics, including the following:

- Demonstrating a stable track record. While this principle is less relevant in expansion capital scenarios where growth is a more important consideration and it doesn’t strictly apply in turnaround scenarios, typically PE will be attracted to established businesses with stable track records. That doesn’t mean that a PE target may not be currently underperforming. However, younger companies or those with wildly inconsistent performance histories will be generally seen as too risky.

- Capable of being purchased at an attractive multiple. One of the dynamics that PE uses to drive returns is securing an opportunity at a relatively lower multiple with the view to ultimately exiting at a higher one. That’s what makes traditional leveraged buy-outs of underperforming companies so attractive to PE. If a business is already fully priced, it becomes less attractive to PE.

- Capable of generating strong cash flows. While different PE funds and strategies rely on debt funding to different degrees, a business with strong cash flow generation is an important attribute for PE because it gives greater comfort that a business can sustain a higher level of debt without the risk of experiencing financial distress. It is also a general marker of a more solid business.

- Possessing a strong market position. A company with a strong market position – a unique product offering, deep customer relationships, recognisable brands and so on – in turn enjoys higher barriers to entry, a lower risk of substitutes and greater pricing power. These attributes provide the business with more stable, defensible and predictable cash flows, which in turn lower the risk profile for PE investors.

- Capable of strong revenue growth. A key lever available to PE is the ability to profitably grow revenue. The more quickly that a company can grow, the sooner it can be positioned for an exit. In addition, trade buyers and the public markets tend to pay a premium for companies that can grow at above average rates on a sustainable basis. Therefore, identifying companies with strong and credible growth potential is an important consideration for PE.

- Capable of efficiency enhancement. While being able to grow revenue is an important consideration, PE also looks for opportunities to increase efficiencies and reduce expenses. Indeed, many experienced PE investors &/or members of their teams being strong consulting and operational experience for this purpose. The challenge is to find efficiencies without jeopardising the business’ growth or sustainability.

- Possessing low capital expenditure requirements. All things being equal, the lower a company’s ongoing capital expenditure requirements, the greater its cash flow generating capabilities and the stronger its capacity to manage a higher debt load. Therefore, PE will typically prefer companies with lower capital expenditure requirements, particularly in terms of so-called maintenance capex that is not discretionary. (For more information on the difference between maintenance CapEx and growth CapEx, please click here)

- Possessing a proven management team. PE tend to be investment managers and finance professionals rather than hands-on operators. PE managers do not look to run their portfolio companies day-today. As a result, having a strong management team in place makes a company a more attractive PE opportunity. If the pre-existing management team is weak, the PE will need to secure the services of a new management team prior to committing to the investment.

It is also worth mentioning that there are certain types of businesses that typically do not attract PE investors. These include:

- Businesses involved in sectors that are considered not ethically responsible such as tobacco, weaponry, gambling and so on or those with questionable environmental or social impacts.

- Businesses that are vulnerable to movements in commodity prices such as agriculture or mining. PE prefers to invest in opportunities where they have maximum control over outcomes. Therefore, businesses that are heavily ‘price takers’ are less attractive.

- Similarly, businesses involved in direct property development are less attractive because their fortunes are also heavily tethered to the general business cycle, the availability of credit and so on which are beyond the control of PE.

Platform Versus Bolt-on Acquisitions

It is important to distinguish between what PE describes as a platform investment versus a bolt-on acquisition. A platform investment represents a first investment in a new investment strategy. As a result, a platform investment will not be combined with any existing companies within the PE’s portfolio.

Prior to committing to a platform investment, a PE will undertake a significant amount of fundamental industry research to determine whether it is likely to be a fertile area for the firm to deploy its capital. It’s only once this deep industry research has been completed that a PE will look at specific companies within the industry.

A bolt-on acquisition is a company that is acquired to supplement a platform investment. When looking at a bolt-on, the PE has already committed to the industry through its platform investment as is looking at businesses that will add size and synergistic benefits.

While a PE will conduct detailed due diligence on all investments, the level of analysis that goes into making a platform investment is necessarily deeper than it is with a bolt-on. Bolt-on’s build on the hard work that already went into making the platform investment.

In addition, normally platform investments will be significantly larger than a bolt-on. The platform needs to give the PE the opportunity to gain a sufficient foothold in a given industry to start to scale as well as provide the immediate chance to deploy sufficient capital to make the investment economically worthwhile.

How Private Equity Firms Drive Returns

To fully understanding the types of opportunities that private equity is interested in, it is useful to explore how PE firms generate their returns by looking at the lifecycle of a simplified PE investment.

Example:

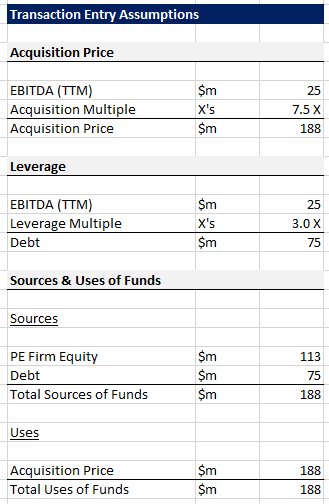

Let’s say that hypothetical PE firm, Hibiscus Capital, has just bought 100% of the shares in medical imaging company, X-PIC Pty Ltd. At the time of acquisition, X-PIC Pty Ltd had EBITDA for the trailing 12 months (TTM) of $25.0m and was purchased on an EBITDA multiple of 7.5X’s. In addition, Hibiscus completed the transaction by borrowing at 3.0X’s EBITDA.

To complete the $188m acquisition, Hibiscus Capital borrowed $75m and invested $113m of its own equity.

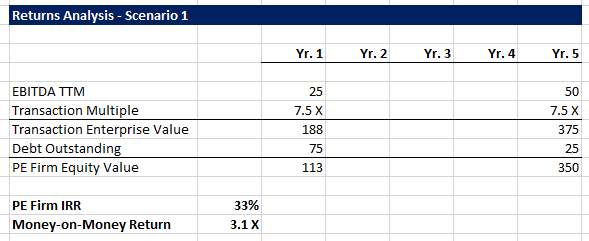

Let’s now assume that Hibiscus was able to exit the investment after five years at the same multiple of 7.5X’s EBITDA. Let’s assume further that during the PE’s involvement, EBITDA had doubled to $50m and debt had been paid down to $25m. Based on these assumptions, Hibiscus would extract an internal rate of return (“IRR”) pre-fees of 33% and a money-on-money return of 3.1-times.

The private equity firm generated a profit of $238m (ie. $315m – $113m) on its investment in X-PIC Pty Ltd. Assuming the firm’s general partners were entitled to a success fee of 20% on that profit, they would notionally receive a fee of $48m.

However, let’s assume that a 33% IRR is deemed below expectations. What potential levers does the firm have available to boost that return? There are several:

- Further growing earnings through operational improvements such as cost savings and revenue initiatives;

- Loading up X-PIC Pty Ltd with a higher debt load at the beginning of the transaction &/or paying off more debt during the life of the investment;

- Negotiating a lower entry multiple at the time of acquisition and securing a higher exit multiple;

- Achieving an exit more quickly to benefit from the time-value of money.

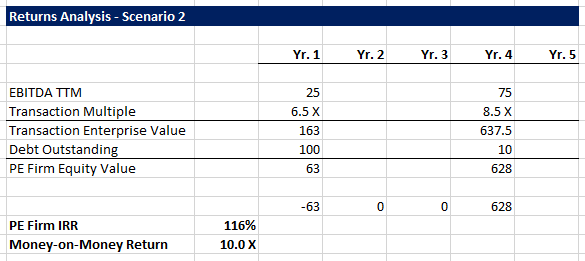

Let’s look at the impact of all of these “levers” on IRR. Assume Hibiscus bought in at 6.5-times EBITDA rather than 7.5-times and borrowed at 4.0-times EBITDA rather than 3.0. Assume further that an exit was secured a year earlier and at 8.5-times EBITDA instead of 7.5, that EBITDA was $75m at exit and debt was down to only $10.0m.

This revised scenario has a profound impact on investment’s returns with the IRR on the deal growing from 33% to 116%.

The private equity firm’s general partners would potentially be entitled to a success fee of $113m. Not bad for four years’ worth of work!

This example illustrates the various levers that PE firms can try to use to drive returns. The four key levers are: negotiating hard to secure a favourable entry multiple; taking on enough debt to drive returns without risking the company’s solvency; focusing on operational improvements to boost earnings; and working fast to position the company for an exit as soon as possible.

Typically, PE firms do not have any real control over the prevailing exit multiples that will be on offer at the time of an exit and, therefore, prefer not to rely heavily on this lever.

Looking Closer at Leverage

Another related consideration for private equity firm’s is a company’s debt-carrying capacity. While different firms have differing appetites for overall levels of debt, traditionally, PE has relied at least in part on utilising leverage to drive returns. As we saw in the example above, the more debt that is used in a deal, the less equity a PE firm needs to deploy and the higher their potential returns.

This raises the very important point from a PE’s perspective in relation to cash flow, and particularly free cash flow. Free cash flow is the amount of cash left over to service debt after a company accounts for the capital expenditure needed to maintain its asset base.

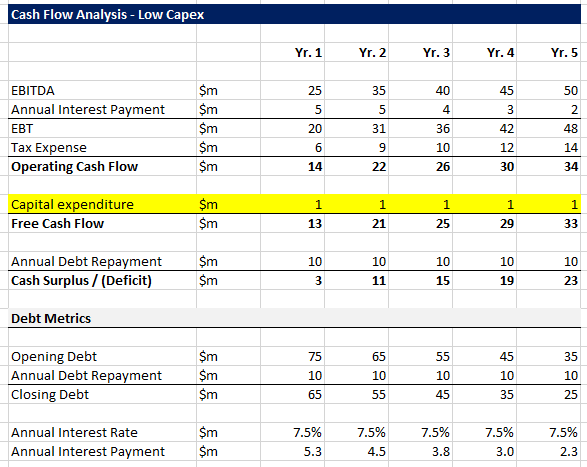

Let’s assume that in Scenario 1 above, X-PIC Pty Ltd has a low ongoing requirement for capital expenditure, even if that would most likely be unrealistic for a medical imaging company.

In this circumstance, a scenario of borrowing at 4.0-times EBITDA and repaying principal at a rate of $10m per year is possible in so far as the company maintains a positive cash surplus after debt repayment.

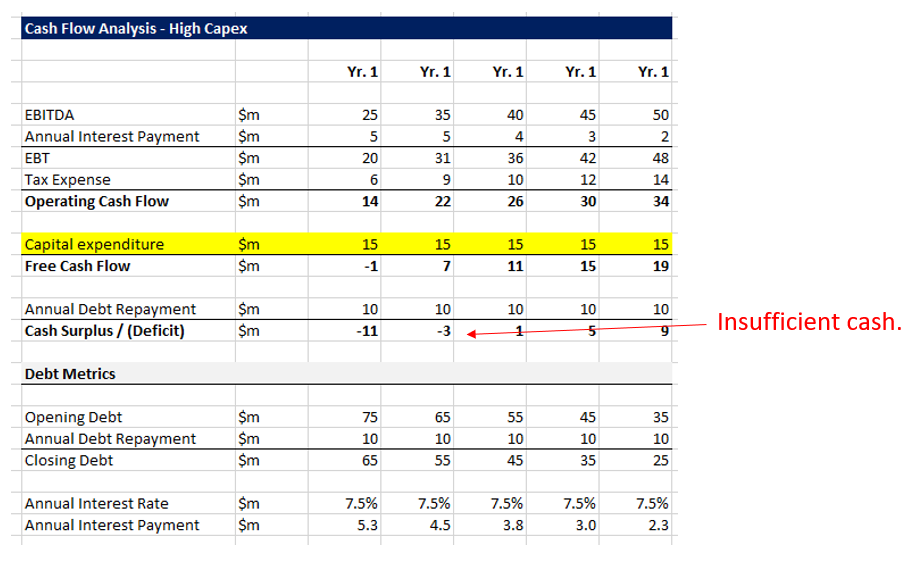

However, if the company had a significantly higher capital expenditure requirement in order to maintain the company’s competitive position in the market as a leading-edge medical imaging provider, the acquisition scenario of 4.0-times EBITDA simply would not stack up.

What this very simple example demonstrates is that private equity will pay particularly close attention to a prospective investment’s cash flow forecasts, including capital expenditure, and the implications they have for the company’s debt-carrying capacity.

Private equity is an important potential acquirer for businesses in the Australian market and it is, therefore, important to understand what types of opportunities sit within their “sweet spot.” If you would like to have a confidential discussion about how CFSG can assist you in successfully preparing for and completing the sale of your business, please contact us.