Our latest news and analysis.

Why growth capital investors tend to prefer lower capital intensity businesses.

When it comes to raising capital from growth capital investors, there are certain characteristics of a business that make one opportunity relatively more attractive than the next.

One of those characteristics is the capital intensity of the business, which refers to the proportion of fixed assets that the business relies on to produce its goods and services. A business that is capital intensive requires a relatively larger proportion of fixed assets such as property, plant and equipment (“PP&E”).

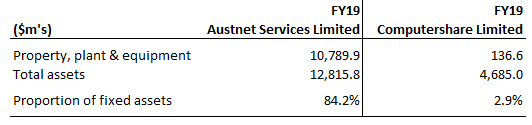

This phenomenon is demonstrated in the screengrab below that shows the relative proportion of PP&E between two companies: Ausnet Services and Computershare.

Given that Ausnet owns and operates large-scale electricity infrastructure (ie. “poles & wires”) whereas Computershare provides software solutions to manage companies’ shareholders, the disparity in PP&E is not surprising.

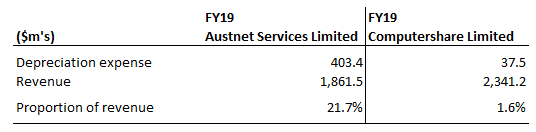

One of the indicators or consequences of a capital-intensive business is a relatively high level of depreciation. Depreciation is financial accounting’s way of recognising that the value of fixed assets is depleted through use and obsolescence over time.

This phenomenon is demonstrated in a further comparison of the profit & loss statements of Ausnet and Computershare.

Clearly, depreciation plays a far larger role in Ausnet’s business than it does for Computershare, which again is unsurprising given the significant disparity in PP&E between the two companies.

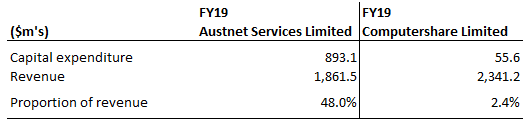

The implication is that from one accounting period to the next Ausnet is going to be ‘wearing and tearing’ far more PP&E than Computershare – value that Ausnet is going to need to replace if it is going to maintain its productive capacity. That replacement takes the form of capital expenditure (“CapEx”).

(For more detail on the types of CapEx and why the various distinctions are important, click here).

And therein lies the reason why growth capital equity investors tend – all things being equal – to prefer companies that are relatively less capital intensive: they generally require a far lower commitment to ongoing CapEx.

Why does that matter?

The reason is that growth capital investors – like all investors – are looking to achieve the highest possible return on their invested capital over time. The more capital intensive a business, the greater that business’ ongoing CapEx requirement, which must somehow be financed.

At its most basic, the more capital intensive a business, the more capital an investor will need to commit to the business and the lower will be the business’ return on invested capital.

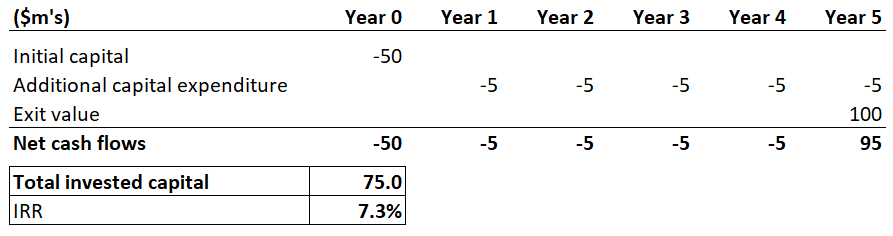

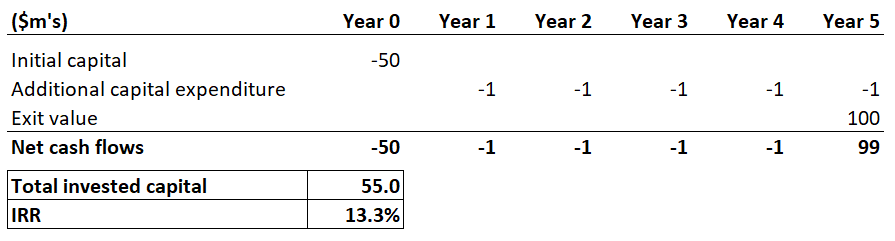

Let’s contrast two competing investments: Investment A and Investment B. Both investments require an initial outlay of $50.0m and are expected to recoup $100.0m over a five-year holding period. The only difference between the two is their respective ongoing levels of CapEx.

Investment A has relatively low capital intensity and only requires the investor to annually contribute $1.0m of additional capital to the business to meet its ongoing CapEx requirements. In such circumstances, the business will earn an internal rate of return (“IRR”) of 13.3% over five years as shown below.

It is worth noting that the pattern of CapEx investment above is unrealistic. CapEx tends to be “lumpy” in that fluctuates from one period to the next. Major pieces of PP&E tend to only be purchased periodically.

Let’s now look at Investment B that requires an ongoing CapEx commitment of $5.0 per year over the life of the investment. That additional CapEx has a significantly negative impact on the IRR that is achieved – it declines from 13.3% to 7.3%.

That’s almost a 50% decline in return on investment solely due to a difference in the capital intensity of the respective businesses.

The above analysis is, indeed, highly simplistic. An obvious response would be that a business does not have to fund ongoing CapEx by raising additional equity capital. Rather, a company can fund CapEx out of its existing cash balances, from operating cash flow or through borrowings.

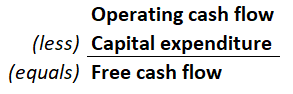

This is the concept of “free cash flow”, which a key metric in private equity.

Free cash flow refers to the operating cash flow available after a company meets its CapEx requirements. What is clear is that the higher a company’s CapEx requirements, the lower its free cash flow.

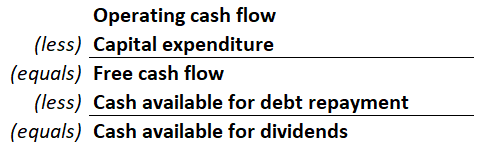

A company with lower levels of free cash flow necessarily generates less cash with which it can repay debt. That means that such a company must rely relatively more heavily on equity funding. As we saw above, the more equity investors must tie up in a business, the lower their returns.

Furthermore, the lower the levels of a company’s free cash flow, the less cash that is available for a business to pay the owners a dividend after periodic debt commitments have been met. The payment of dividends is another way in which investors can boost returns over the life of an investment.

What the above highlights is that all things being equal, a business with greater capital intensity will result in lower returns on invested capital. That is why growth capital investors often prefer to invest in businesses with lower CapEx requirements.

If you would like to discuss how CFSG can assist you navigate your way towards securing investment for your growing company, we invite you to contact us.